The color black -

Charred wood as a façade trend, the “why & how”, and the impact of black façade surfaces in the public realm.

TEKST som diskuterer opplevelsen av fargene på byggene rundt oss opp mot trenden med kullsvarte fasader. Essay fra våren 2016 skrevet av Nina Haarsaker i samarbeid med Kine Angelo, Arnstein Gilberg og Guro Wiksten Brenk ved AD, NTNU.

ABSTRACT//

CHARRED WOOD AND THE COLOUR BLACK

Natural surface treatment, like charred wood, is quickly becoming a new trend. All building materials have specific material qualities, and all materials have colours - i.e. the inherent colour of wood or applied colour to achieve a specific material quality or look. This text explains and examines traditional use of charred wood, interesting cultural and technological aspects and in comparison to other traditional surface treatments through questions as:

What is black? How common is the use of black on facades historically in Norway, and what does black facades imply in modern urban realms? – to how and why is the charring of wood made, what do we know and what could be investigated further on?

CHARRED WOOD AND THE COLOUR BLACK | text contribution compiled spring 2016 by Kine Angelo, Guro W. Brenk, Arnstein Gilberg, Nina Haarsaker | NTNU

THE COLOUR BLACK

What is black

Basically, what we perceive as colours are light in specific wavelengths and the perception of colours are influenced by the properties of the surface reflecting the light to the eye. The surfaces ability to absorb, transmit or reflect determines the colour, and the surfaces ability to reflect or diffuse the light determines the intensity of the colour. The colour black can be described both as absence and presence of colour, depending on whether we're talking about emitted light and additive colour mixing, or pigments and subtractive colour mixing.

It is the contrasts between objects, and between object and background, that allows us to see, to orientate and to gather information about our surroundings. Human vision allows us to see contrast in lightness provided by light levels, and our colour vision provides the additional ability to see contrasts between colours. The main tasks of colour vision can be said to enhance contrast or to blend in.

The eye is always drawn to the highest contrast in our visual field, i.e. light level or colour intensity. Example of maximum contrast is between the achromatic colours black and white, and especially in combination with a high intensity of a chromatic colour, best exemplified by looking at traffic signs (black and bright red on a white background, or the combination black and bright yellow).

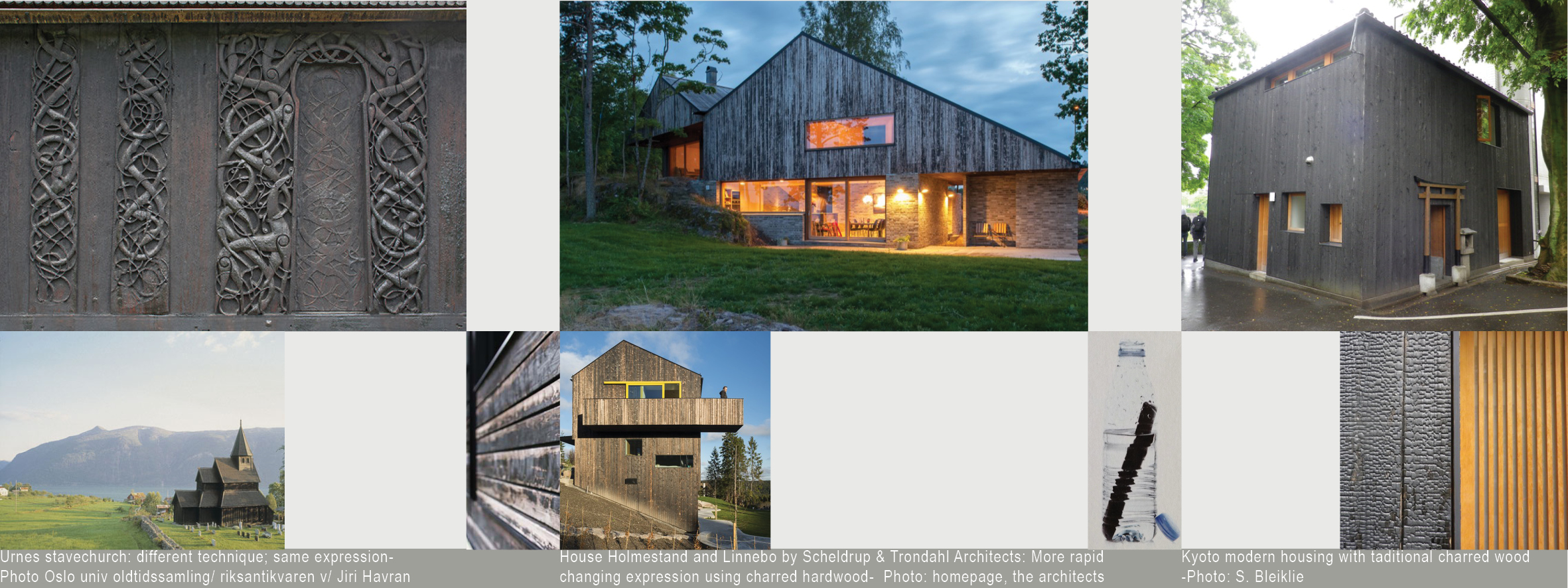

Traditional use of black as a façade colour

Façade colours have traditionally been a result of both aesthetical and practical reasons, by available building materials, pigments and binders and the need to preserve the building against the elements. By choosing the building material, it both affords and dictates the choice of colours. Firstly, different materials have different inherent colours. Secondly, materials requires and affords different treatment suited for the specific material properties, thus giving it a specific col-our, such as the technique of charring wood. Thirdly, even if painted with the same pigment, the properties of the material surface - or the suitable binder for the pigment - will influence the perception of the colour on the facade.

If black is considered through the lense of Norwegian tradition and cultural identity, black façades were traditionally a result of wood preservation using different types of tar, resulting in a typically a black, matte surface. These buildings are still present in the cultural landscape, most noticeably in the valleys of Gudbrandsdalen, where they sit high up in the steep, dark mountainsides or against dark fir forests, or on old churches (stavkirker), the blackness contributing to visually added volume and height. All over the country, traditional, low mountain cabins are still being treated or painted to get a black colour.

In principal, if a surface absorbs all the wavelength, it reflects nothing back to the eye and we perceive it as black. Some of the light emitted by the surface is converted to heat in the material. In buildings, this can help reduce need for heating. This design element in the use of black as a façade colour has in recent years been used in the development of Active and Passive houses.

Contemporary use of black as a façade colour

As of today, Norway is foremost associated with the traditional timber cladded and rendered buildings in hues of medium to bright nuances of yellows, reds and greens, in unison with buildings with inherent colours of stone and brick. With few exception and in rural areas, black buildings rarely featured in architectural history until modernism in early to mid-1900 century. Still, they were few and far apart, and the black facades were not overly dominated by the dark colour, but softened by the extensive use of more reflective, transparent or translucent ma-terials. In the evenings, these buildings appear as open as they appear closed during the height of the day, and their location and significance usually give more room for open spaces around them, much like the old stavkirker.

Until this time, building typology and materials had not changed dramatically thorough the history, and neither had our primary sources and choices of façade colours. However, around 1950, this changed in staggering rapidity. Modernism as an architectural style, was most suitable for industrialisation in a time when rapid, cheap building was necessary. New materials and paints became available, and buildings and cities increased in volume, density, width and height.

Contradictory to being allowed a choice of a wider range of façade colours than ever before, the use of chromatic colours are decreasing in favour for the achro-matic colours white, grey and black.

Black as a façade colour and a design element in architecture is the newest trend, following white and grey. It is now used as wood treatment, such as charred wood, as choice of paint colour due to maintenance or when building with façade panels, or as inherent colour of glass and stone materials, and fore-most in the urban environment.

Black as a façade colour in the urban realm?

Keeping the increasing density of the cities and the increasing height and width of the buildings in mind, we have examined buildings in the center of Trondheim, existing black buildings and new buildings planned with black facades.

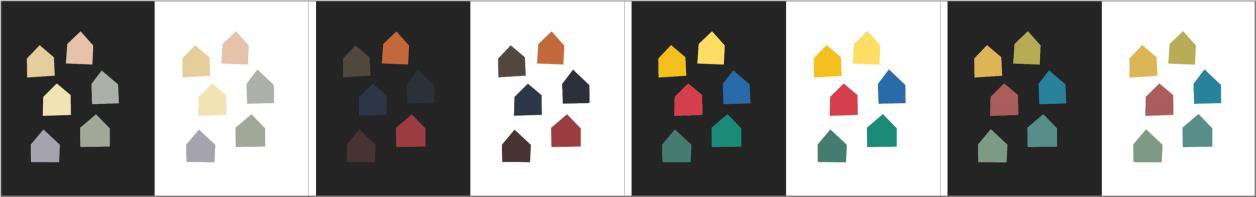

We have compared this development with what we know about the properties of the colour black, how we perceive it in the overall gestalt and how the colour black relates to our cultural identity. The reasons given for choosing black as the colour as the façade rarely relates the it’s beneficial properties to sustainable gain, and we have not found relevant research as to what this might do to a city as a whole, its cultural identity or visual clarity within the cityscape.

In rural areas, black facades might blend in with the landscape of mountains, hillsides and dark evergreen forests, but in most urban realms black is most like-ly to contrasts greatly with the traditional colours of the existing building mass or against the surrounding colours during summer- and daytime. In wintertime and during night, it blends perfectly in with the surrounding sky, but is more likely to create black holes between existing buildings. As black reflects little or no light, dense building areas are not aided by reflecting light in narrow alleys. If this trend gets the same widespread use as the white or gray façade colour, we might soon need to add artificial lighting, to make up for the light lost by the choice of colour.

For her work in Longyearbyen, Grete Smedal conducted a study to find which colours were best visible throughout a year, concluding it to be the chromatic colours of more or less the same likeness to white, black and chromatic colours. This to achieve contrast to the surrounding not too strong nor too weak for good visual clarity. Using her method, we have tested how well we see Trondheim’s traditional fasade colours and the more contemporary whites, greys and black colours, seen against four typical background scenarios for the city. Our conclu-sions are the same as in Smedals study.

The next research study will be the nominal and perceived colour of the colour black in urban environment, not included in this paper, as the study will be con-ducted in February this year.

( See Illustration of Grete Smedals’ study of façade colours seen against background, by Kine Angelo).

CHARRING OF WOOD SURFACES

What is charred wood

The technique of charring 2-5 mm of surface of solid wood or siding, is best known from Japan as yakisugi *. The word “Yaki“ means burn, and “sugi“ means cedar. Cedar is in the family of softwood/coniferous wood as pine, spruce and cypress. The main use of sugi in traditional Japanese architecture was for roof-ing, because sugi (Cryptomeria Japonica), has properties making the splitting into boards and shingles convenient. (”Architectural preservation in Japan” Knut E. Larsen, NTNU,1994).

(* In commercial context in the western world, the expression “shou sugi ban” is often used instead of yakisugi for the same technique. Our Japanese source, Ar-chitect Daigo Ishii / Future-scape Architects, says there is no word pronounced as shou sugi ban. Japanese is different from European Languages in the way that most of Japanese letters have various pronunciations for one letter. Shou sugi is a wrong combination of pronunciation of each letter that composes Yaki sugi. The Japanese letter of Yakisugi is possible to read as shou sugi, and ban means board. But, the letter is not pronounced as shou sugi, but yakisugi.)

Why char the wood surface

One argument for charring wood, like the goal for all surface treatment of wood, is that it lengthens the life span of the material. Advertising on internet for char-ring, is that it is «UV resistant, weather-resistant, rot and bug resistant, and it can last for 80 years or more with little or no maintenance”. At the same time, no one will guarantee of the life span of commercial façade material, since this is largely depending on usage and detailing, in addition to possible variation in the quality of the material itself. In commercial advertising on internet, we have not found any reference to research. We lean in this case on communicated silent knowledge, and the claim that untreated construction and paneling, with good materials and detailing, can work for centuries if it is left dry and free from destructive radiation and abrasion.

Significant archaeological discoveries has found coal residues in cooking pits, fireplaces or fire ruins. Where all other organic material is gone, they have found coal materials lasting for more than 1,000 years. Burned or carbonized wood is a familiar way to prevent rot and fungal growth in wood materials, and this technique for preserving wood has a long tradition in Norway. Fence posts shortly burned over an open fire so that it formed a powerful team with charcoal, crackled and with a characteristic gray color. The charred wood acts as a protective layer for the section of the bar or stance which is in direct contact with soil. The method has been thoroughly tested and approved to prolonging the lifespan of a fence posts. Meaning- the part of posts attached into soil or the ground are charred in advance- likewise in Japan wooden cladding to protect them from termite attack. (Wood and wood joints, Building traditions in Europa, Japan and China, 2012). However, we have found no documentation on using charring of wood as a preservative for façade materials in traditional Norwegian architecture.

The charred surface is less interesting for microorganisms - thus providing some protection – as the loosest/softest and most attractive part of the wood burned away. This leaves the harder material with winter-rings, knots from branches, and forms a protection for organic material within. Before washed out, the ash perform alkalized, and this in addition has a beneficial effect in an acidic environment. The result is a burned, dark façade that absorbs solar heat and dries up quickly, and combined with appropriate detailing with good aeration and drainage, charred wood gives an effective, maintenance-free facade for many years.

How to char the wood?

Traditionally, the most effective way to char panel, using low energy supply, is by rising (buoyancy) of air, and the chimney effect. (See traditional yakisugi on Japanese television: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xoBjpXOlyM). By taking three panels of same length tied together, making a wooden pipe, this is easy to do. This pipe is put on top of a small fire. The chimney must be turned upside down after a few minutes, so that the entire surface on the inside is evenly burnt. Finishing one chimney with 2-4 mm charred surface, takes approximately 5 minutes. To stop the fire, the pipe is disassembled and sprayed with water from for example a garden hose.

Commercial small-scale industry is likely to use gas. Largescale grilling of panels also is tested. One challenge with gas and grilling, is giving enough effect for the charring. Uncertain what is the main reason, but using hardwood like aspen and horizontal paneling together with to superficial charring, is risking flakes shaving off after short time. (NGBC,2015). To get more knowledge, we have followed two projects in Trondheim. One with pine siding charred with the under mentioned chimney-fire-technique built in 2014, and the other with siding of local spruce, gas-treated and painted with linseed oil, completed in 2016.

Who is charring?

In Norway only two known stakeholders have invested in the technique. Several companies in the western world have jumped on the trend and started commercial production of charred wood siding. Those with the most comprehensive information is a website from the US firm CharredWood using cypress or red cedar, with facts on “What makes charred wood pest and bug resistant?», «What is the history of charred cedar/ Yakisugi/Shou Sugi Ban treatment» and « how does charring make wood fire resistant». (Http://charredwood.com/ , 2017).

How environment-friendly is this technique

The choice of facade material provides great environmental effect. The material should have as little bound energy as possible, and locally produced three-cladding of high quality is one of the best choices you can do (Bygg.no, 2014). The Environmental Product Declaration, EPD, doing life span analysis (LCA) on locally produced and untreated ore-pine as facade material with a lifespan of 60 years have a very low, down to 1 Co2 emission pr.m2, compared to a painted facade repainted every 6-10 years, which is measured to between 8-14 CO2 pr.m2 for the same length of time. (Åsveien Skole Flerbrukshall, Eggen ar-kitekter. 2016). Charring the surface is off course releasing some of the bound energy, compared to untreated panel. There would be emissions savings in terms of replacement due to the fact the charring of the wood would mean the wood would not need to be replaced. So, if cladding had a lifetime of say 15 to 20 years and you were calculating for 80 years, then you would reduce replacement emissions by one forth an estimate. Secondly, there would be savings due to the amount of paint required. The amount of paint spared can easily be associated with emissions savings.

Further investigations

A FUTURE FURTHER INVESTIGATION should discuss and examine the advantages and disadvantages of the use of charred wood. An proposal is using four housing projects of different typologies, with critical references to practical and aesthetical values, e.g. the impact black façade surfaces might have on cultural identity and our perception of spaces the public realm.

References:

Larsen, Knut Einar. ”Architectural preservation in Japan” (1994): page 89

Zwerger, Klaus. “Wood and wood joints, Building traditions in Europa, Japan and China. Second, Revised and Expanded edition.” (2012): page21

Haarsaker, Nina. Gjerde, Sevrin. “Årstidshuset”: http://aarstidshus.blogspot.no/ (2014):Web.

Yakisugi done traditionally on Japanese television:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xoBjpXOlyM (2011):Web.

Norwegian Green Building Council, Powerhouse at Kjørbo, http://ngbc.no/portfolio-items/powerhouse-kjorbo-2/#iLightbox[dc68d12109b39b87c3c]/0 (2015 NGBC): Web.

CharredWood. Http://charredwood.com/ (2017):Web. Strand, Sindre Sverdup. Websiden til Bygg.no, http://www.bygg.no/article/1186020 (2014):Web.

Solem, Bård. Eggen arkitekter. «Åsveien skole flerbrukshall» (2016), page 52.

Smedal, Grete. “The Colours of Longyearbyen – an ongoing project” ( 2009), Eget forlag,

Bergen.

Valberg, Arne. “Light Vision Color” (2005). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.